The Difference Between a Lead Seller and a Lead Business

Most companies that sell leads believe they are running a business.

Many are not.

They are operating a transaction loop that happens to be profitable in the moment.

That distinction matters more now than ever. Traffic costs continue to rise. Buyer churn is accelerating. Compliance risk is no longer theoretical. At the same time, AI-driven efficiency is raising expectations around speed and quality.

After nearly two decades working on both sides of this industry, running lead generation operations and building the infrastructure that supports them, a clear pattern emerges:

Lead sellers survive months.

Lead businesses survive years.

The difference is not effort, creativity, or ambition.

It is operational design.

A Lead Seller Optimizes for Today

A lead seller focuses on the immediate transaction.

Generate leads at the lowest possible cost.

Sell them quickly.

Maintain buyer satisfaction in the short term.

This approach is common and often necessary in the early stages. Most lead companies start this way.

The problem is what follows.

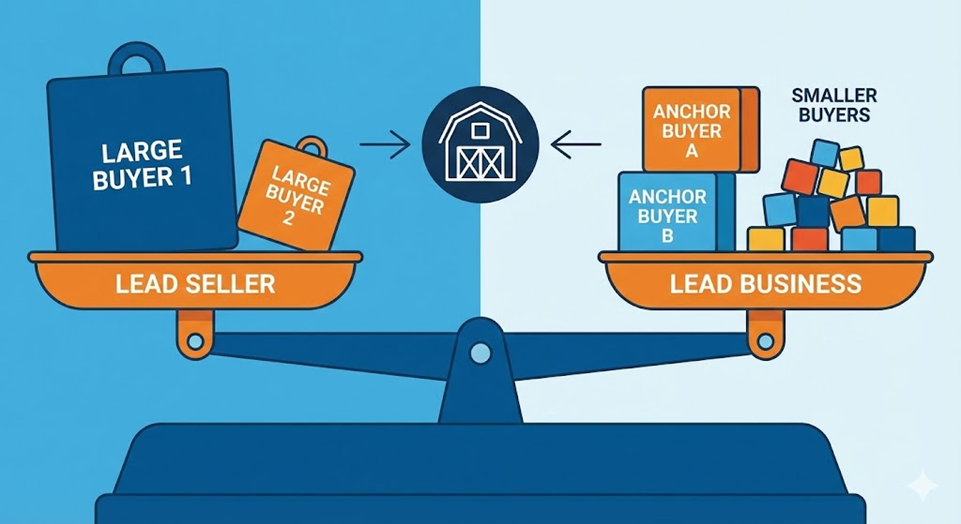

Lead sellers tend to develop extreme revenue concentration. One or two large buyers typically drive the majority of the volume. Pricing, routing, and internal processes quietly adjust to keep those accounts active.

Lead sellers tend to share a few characteristics:

-

Revenue is concentrated in one or two buyers

-

Pricing decisions are reactive

-

Routing rules are fragile and manually adjusted

-

Performance issues are discovered through complaints, not data

-

Compliance is handled “well enough” until it isn’t

It works until it no longer does.

A Lead Business Designs for Revenue Stability

Lead businesses approach revenue the way mature SaaS companies do.

There is a reason most SaaS founders are encouraged to start with SMBs before pursuing enterprise contracts. Enterprise revenue is attractive, but it is fragile. When eighty percent of revenue is tied to two or three accounts, losing just one creates immediate risk.

Instead of asking “How do we sell more leads this month?” a Lead Business asks:

-

What fails first when volume doubles?

-

Where does margin silently leak?

-

Which buyers help us scale, and which ones quietly hurt us?

-

How do we make the operation resilient, not just profitable?

This is not just anecdotal. In SaaS and recurring-revenue businesses, customer concentration is widely recognized as a structural risk. As L40, a growth advisory firm focused on SaaS and recurring revenue models, explains:

“Customer concentration risk occurs when a large share of revenue depends on a small number of clients. While large accounts can accelerate growth, they also create exposure. Diversifying the customer base improves predictability and reduces volatility.”

Lead generation companies face the same dynamic.

A few large buyers can feel like success, but they create single points of failure.

A lead business avoids this by designing a buyer portfolio rather than maintaining a simple buyer list.

That portfolio typically includes:

- Several large, high-volume buyers that anchor revenue

- A long tail of smaller buyers that absorb overflow

- Automated onboarding and delivery so smaller accounts remain profitable

This structure protects revenue when a large buyer pauses, creating a pipeline of smaller buyers that can grow into larger accounts over time.

Scale Requires a System, Not Just More Buyers

Lead sellers add buyers manually.

Lead businesses add buyers systematically.

That requires infrastructure that supports:

- Self-service buyer onboarding

- Standardized delivery logic that applies across accounts

- Automated pricing, caps, and throttles

- Clear performance visibility by buyer tier

Smaller buyers should not require more effort per lead than large buyers. If they do, the system will not work. This means you must account for automation; you cannot process manual orders for leads.

When infrastructure is designed correctly, smaller buyers stabilize the business. They smooth volume fluctuations, reduce dependency risk, and provide leverage in enterprise negotiations.

This is the same revenue security model used by successful SaaS companies. A broad base creates predictability. Enterprise scale becomes additive rather than existential.

Systems Replace Heroics

Lead sellers rely on individuals to keep the operation running smoothly.

Lead businesses rely on systems.

Routing rules live in software, not in personal knowledge.

Buyer rules are enforced automatically, not negotiated repeatedly.

This is how growth occurs without fragility.

Performance Is Measured, Not Assumed

Lead sellers talk about lead quality.

Lead businesses measure outcomes.

They track:

-

Contact rates by buyer and source

-

Time-to-first-attempt decay

-

Conversion deltas between buyers receiving the same leads

-

Refunds, disputes, and churn as early warning signals

This data drives pricing decisions, throttling logic, and volume allocation. High-performing smaller buyers receive increased volume. Poor performers are limited before they create downstream damage.

Over time, performance data improves the system itself.

Compliance Is Embedded, Not Added Later

Compliance follows the same pattern.

For lead sellers, it is often addressed after delivery.

For lead businesses, it is part of the intake.

Consent handling, including TCPA compliance, suppression logic, and auditability, is standardized across all buyers, regardless of size. This removes compliance as a variable tied to influence or revenue contribution.

Risk is managed consistently and proactively.

The Real Difference

A lead seller grows until something breaks.

A lead business grows because it planned for what would break.

The companies that survive are not the ones with the largest buyers. They are the ones with the most resilient systems.

After twenty years in this industry, the lesson is consistent:

Selling leads is a transaction.

Building a lead business is an architectural decision.

The companies that understand this early on grow with confidence, negotiate from a position of strength, and survive the market shifts that quietly eliminate everyone else.

Perspective from Practice

This perspective stems from working with lead generation companies as they transition from opportunistic growth to sustainable operations. Across teams at different stages, the same inflection point emerges: volume increases, buyer concentration tightens, and the limitations of manual routing, informal rules, and reactive decision-making become apparent.

At ClickPoint Software, we observe the contrast between lead sellers and lead businesses unfold within real systems. Teams that treat lead delivery as a series of one-off transactions tend to accumulate fragility—custom rules, buyer exceptions, and undocumented decisions that only work while conditions remain stable.

LeadExec was built to support lead businesses rather than transaction loops. By centralizing intake, standardizing routing logic, enforcing buyer rules automatically, and tying performance and compliance data to every delivery, teams can design for resilience instead of reacting to breakage. This system-first approach allows revenue to scale without concentrating risk, embeds compliance at the operational level, and replaces heroics with repeatable infrastructure.